Misidentified Villain – The Case for Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette enjoys almost universal name recognition for all of the wrong reasons,

since the French Revolutionaries successfully cast her as a pretentious, unfeeling,

coquettish, and superficial queen, with no regard for the plight of her subjects who

were suffering under the pressure of French absolutism. Even as the Revolution’s machine

worked to end her life, she didn’t even receive the same kind of quiet dignity as

her husband, Louis XVI, whose one-way journey to the guillotine was in a fine carriage.

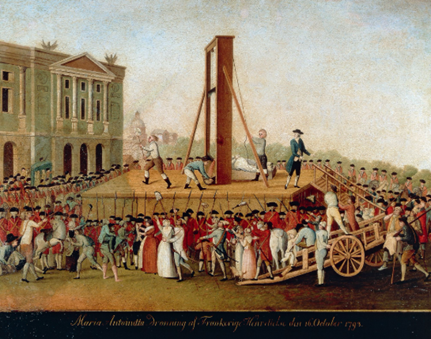

In contrast, hers was in an open cart, thereby allowing all of Paris to throw objects

and insults at her in one final humiliating scene. The popular hate for Marie Antoinette,

however, is rooted in mythology and misunderstanding.

Marie Antoinette enjoys almost universal name recognition for all of the wrong reasons,

since the French Revolutionaries successfully cast her as a pretentious, unfeeling,

coquettish, and superficial queen, with no regard for the plight of her subjects who

were suffering under the pressure of French absolutism. Even as the Revolution’s machine

worked to end her life, she didn’t even receive the same kind of quiet dignity as

her husband, Louis XVI, whose one-way journey to the guillotine was in a fine carriage.

In contrast, hers was in an open cart, thereby allowing all of Paris to throw objects

and insults at her in one final humiliating scene. The popular hate for Marie Antoinette,

however, is rooted in mythology and misunderstanding.

Marie Antoinette was the daughter of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, whose power in Central Europe was slowly eroding as the Holy Roman Empire’s decline was imminent. One of Maria Theresa’s strategies to elevate her family’s position was through carefully calculated marriages, and the wedding of Marie Antoinette to the French King Louis XVI afforded such promise. Though the French and Austrians had been sworn enemies for decades, the marriage was the ultimate symbol of a new alliance system in Europe between France and Austria, albeit unfamiliar and arguably unpopular with many in France, having grown so accustomed to seeing Austria as the enemy. So, it is in this context that the 14-year-old Marie Antoinette left her family behind and headed for France, doomed to be the symbol of an unpopular alliance, and essentially an easy target for anyone who loathed monarchy as an institution. She would never see her family in Austria again – a fact she lamented frequently in her letters to her mother.

It is here that Marie Antoinette underwent a drastic transformation from a shy Austrian princess to being fully immersed in the French Court as a means of preparing her to become the Queen of France. It is fair to describe her existence as one of privileged isolation, and she would have had no opportunities to understand what daily life was like for her subjects. Today, our modern conceptualization of monarchy is perhaps tied to images of the current King Charles III of England shaking hands with his subjects in an effort to be present and available, but such behavior would have been utterly foreign to the 18th century. Generally, kings and queens of the 18th century did not frequently engage their subjects, to say nothing of sympathizing with their condition, or entertaining their concerns, and least of all in absolutist France. However, the idea of sole and uncontestable authority vested in the hands of a ruler, which is the definition of absolutism, can only be sustained if the exercise of this power is unchallenged, and Marie Antoinette found herself in the unfortunate condition of being Queen of France when this power was being questioned.

Yet, as an 18th-century French Queen, Marie Antoinette’s main responsibility was to be admired – to be beautiful, charming, and, most important of all, to produce a dauphin – the male heir to the French throne. She fulfilled all of these expectations. Her happiest years were those spent in the Petit Trianon on the grounds of Versailles, where she certainly engaged in private indulgences, such as gambling – her favorite – and adorning herself in beautiful clothes and jewelry in the kind of resplendence one would expect of a queen. However, she also took a command role in the raising of the daughter who survived to adulthood, Maria Therese Charlotte. Her two sons, she knew, would be completely in the hands of the French Court, who would see to their education and training for the French throne, thereby affording little opportunity for Marie Antoinette to influence their upbringing. Her engagement in politics was nonexistent, and her priorities resided in domestic affairs and the tragedies that befell her with the death of an infant daughter and the loss of her firstborn son to tuberculosis when he was just seven years old. Marie Antoinette, consumed with her own life, would not have been cognizant of the daily struggles of her French subjects, and was never advised or conditioned to do so. Swept up in the frenzy of the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette was a victim of the style and system of rule that was placed before her, perhaps only guilty of playing the role that was given to her too well.

As the 37-year-old Marie Antoinette ascended the scaffold where the guillotine stood in gruesome command, her thoughts were with the young son and daughter who survived her. Her death neither satisfied anyone nor resolved anything, since tens of thousands more would die as the French Revolution continued to unfold in the years ahead. For students of the French Revolution, the absence of monarchy in France was but a brief segment of the saga, since the reign of Napoleon reignited the mystique of monarchy under a new veil of nationalistic triumph. Yet, the last Queen of France – executed 232 years ago this month – reminds us of the fragility of institutions and the vanity and violence that can come with political upheaval.

Dr. Angela Ash, a Professor of History, has been a full-time faculty member at OCTC for nearly 14 years. She is also the History Coordinator for OCTC, the Heritage Curriculum Chair for KCTCS, and the OCTC Hager Scholars Program Coordinator. In addition, Dr. Ash is working on her second doctoral degree, and serves as president of a local non-profit, the Owensboro Area World Affairs Council, whose mission is to advance global understanding in our community. She is also a proud Veteran of the United States Navy.